Visual Cliff Experiment

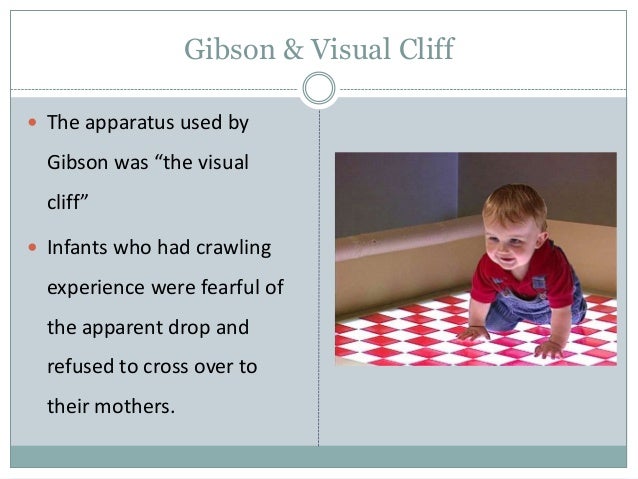

The Visual Cliff experiment was conducted by E. Gibson and R. Walk and they looked in to finding out if children's depth perception is innate or learned. The experiment consisted of a big glass table, which was raised one foot off the floor; underneath half of the glass table a checker pattern was.

Why we’re all just babies on Plexiglas when it comes to interpreting and acting on emotional ambiguity.

By Maria Popova

Living in a highly individualistic culture, we might be tempted to believe we navigate the world as isolated rational actors guided solely by our own perception of reality. But as quantum physics can tell us, everything is connected to everything else — and human psychology is no exception. One of the most fascinating studies of how emotional feedback from others shapes our own perception comes from psychologists Eleanor J. Gibson and R.D. Walk, who in 1960 devised a clever experiment dubbed the visual cliff study: The researchers placed 36 babies, one at a time, on a countertop, half solid plastic covered with a checkered cloth and half clear Plexiglas, on the other side of which was the baby’s mother. To the baby crawling along the countertop, an abyss gapes open where the Plexiglas begins, signaling danger of falling, yet the solid feel of the surface offers ambiguous input. “Will I fall, or will I reach mom?,” the baby ponders.

The researchers found that to make the assessment, the babies relied on the mothers’ facial expression — a reassuring, happy one meant they kept crawling, and an alarmed, angry one made them stop at the edge of the Plexiglas.

When faced with emotional ambiguity, most of us remain babies on Plexiglas — we search for feedback to resolve uncertainty, and often forget that the Plexiglas is there, unflinching — a solid, albeit invisible, support. We just have to take the leap… or crawl, as it were.

For more on the fascinating interplay between our cognition and the emotions of others, see the excellent A General Theory of Love, rereading which reminded me of the visual cliff study.

The visual cliff apparatus was created by psychologists Eleanor J. Gibson and Richard D. Walk at Cornell University to investigate depth perception in human and animal species. This apparatus allowed them to experimentally adjust the optical and tactile stimuli associated with a simulated cliff while protecting the subjects from injury.[1] The visual cliff consists of a sheet of Plexiglas that covers a cloth with a high-contrast checkerboard pattern. On one side the cloth is placed immediately beneath the Plexiglas, and on the other, it is dropped about four feet (1.2 m) below. Since the Plexiglas supports the weight of the infant this is a visual cliff rather than a drop off.[1] Using a visual cliff apparatus, Gibson and Walk examined possible perceptual differences at crawling age between human infants born preterm and human infants born at term without documented visual or motor impairments.[2]

- 2Human infants studies

- 3The study in different species

The original visual cliff study[edit]

Henry and Walk (1960)[3] hypothesized that depth perception is inherent as opposed to a learned process. To test this, they placed 36 infants, six to fourteen months of age, on the shallow side of the visual cliff apparatus. Once the infant was placed on the opaque end of the platform, the caregivers (typically a parent) stood on the other side of the transparent plexiglas, calling out for them to come or holding some sort of enticing stimulus such as a toy so that the infant would be motivated to crawl across towards them. It was assumed if the child was reluctant to crawl to their caregiver, he or she was able to perceive depth, believing that the transparent space was an actual cliff.[4] The researchers found that 27 of the infants crawled over to their mother on the 'deep' side without any problems.[5] A few of the infants crawled but were extremely hesitant. Some infants refused to crawl because they were confused about the perceived drop between them and their mothers. The infants knew the glass was solid by patting it, but still did not cross. In this experiment, all of the babies relied on their vision in order to navigate across the apparatus. This shows that when healthy infants are able to crawl, they can perceive depth.[1] However, results do not indicate that avoidance of cliffs and fear of heights is innate.[1]

Visual Cliff Experiment Article

Human infants studies[edit]

Preterm infants[edit]

Sixteen infants born at term and sixteen born preterm were encouraged to crawl to their caregivers on a modified visual cliff. Successful trials, crossing time, duration of visual attention, duration of tactile exploration, motor strategies, and avoidance behaviors were analyzed. A significant surface effect was found, with longer crossing times and longer durations of visual attention and tactile exploration in the condition with the visual appearance of a deep cliff. Although the two groups of infants did not differ on any of the timed measurements, infants born at term demonstrated a larger number of motor strategies and avoidance behaviors by simple tally. This study indicates that infants born at term and those born preterm can perceive a visual cliff and change their responses accordingly.[2]

'Gene' Czerwinski (1927–2010) in 1954, and became noted for producing an 18' speaker capable of producing 130 dB in at 30 Hz, an astonishing level during its time. Cerwin Vega dual 15-inch.Cerwin-Vega was founded as Vega Associates (with later name changes to Vega Laboratories and then Cerwin-Vega) by aerospace engineer Eugene J. Cerwin-Vega sells internationally from two main locations; one in, and the other location in, while manufacturing their pro products primarily in and home products primarily in China. Another breakthrough product, the world's first solid-state, was released in 1957.

Prelocomotor infants[edit]

Another study measured the cardiac responses of human infants younger than crawling age on the visual cliff. This study found that the infants exhibited distress less frequently when they were placed on the shallow side of the apparatus in contrast to when they were placed on the deep side. This means that prelocomotor infants can discriminate between the two sides of the cliff.[6]

Maternal signaling[edit]

James F Sorce et al. tested [7] to see how maternal emotional signaling affected the behaviors of one-year-olds on the visual cliff. To do this they placed the infants on the shallow side of the visual cliff apparatus and had their mothers on the other side of the visual cliff eliciting different emotional facial expressions. When the mothers posed joy or interest most of the babies crossed the deep side but if the mothers posed fear or anger, most of the babies did not cross the apparatus.

On the contrary, in the absence of depth, most of the babies crossed regardless of the mother's facial expressions. This suggests that babies look to their mother's emotional expressions for advice most often when they are uncertain about the situation.[8]

The study in different species[edit]

The visual cliff was not only tested on human infants, it was applied to other species as well. A few of these species included rats, cats, turtles, cows, and chickens.

Rats[edit]

Rats do not depend upon visual cues like some of the other species tested. Their nocturnal habits lead them to seek food largely by smell. When moving about in the dark, they respond to tactual cues from their stiff whiskers (vibrissae) located on the snout. Hooded rats tested on the visual cliff show little preference for either side of the visual cliff apparatus as long as they could feel the glass with their vibrissae. When placed upon the glass over the deep side, they move about as if there was no cliff.[9]

Cats[edit]

Cats, like rats, are nocturnal animals, sensitive to tactual cues from their vibrissae. But the cat, as a predator, must rely more on its sight. Kittens were observed to have excellent depth-discrimination. At four weeks, the earliest age that a kitten can skillfully move about, they preferred the shallow side of the cliff. When placed on the glass over the deep side, they either freeze or circle backward until they reach the shallow side of the cliff.[9]

Turtles[edit]

The late Robert M. Yerkes of Harvard University found in 1904 that aquatic turtles have somewhat worse depth-discrimination than land turtles. On the visual cliff one might expect an aquatic turtle to respond to the reflections from the glass as it might to water and prefer the deep side for this reason. They showed no such preference; 76% of the aquatic turtles crawled onto the shallow side. The large percentage that choose the deep side suggests either that this turtle has worse depth-discrimination than other animals, or that its natural habitat gives it less occasions to 'fear' a fall.[9]

Cows[edit]

The ability for cows to perceive a visual cliff was tested by NA Arnold et al. Twelve dairy heifers were exposed to a visual cliff in the form of a milking pit while walking through a milking facility. Over this five-day experiment the heifers’ heart rates were measured along with the number of times they stopped throughout the milking facility. Dairy heifers in the experimental group were exposed to a visual cliff while dairy heifers in the control group were not. The experimental group was found to have significantly higher heart rates and stop more frequently than the heifers in the control group. Depth exposure did not have any effect on cortisol levels or the ease of handling of the animals. These findings provide evidence of both depth perception and acute fear of heights in cows. This may lead to a reorganization of the way milking factories function.[10]

Visual Cliff Experiment Infants

Chicks[edit]

Two-day-old chicks responded to the visual cliff when tested by PR Green et al. As the depth of the visual cliff below the chicks was increased, the latency for the chick to move towards the incentive, another chick on the far side of the apparatus, was increased while the speed at which they moved decreased. On the other hand, chicks that were given the same incentive to jump over a visible edge, onto the deep side of the apparatus, were less inclined to move at all depths. This illustrates that the absolute depth of a surface and the relative depth of an edge affect behavior differently in chicks.

Lambs[edit]

Lambs are able to stand and learn to walk almost as soon as they are born. Just like chicks, they were able to be tested as soon as they could stand. They did not make one error when tested on the visual cliff. When placed on the deep side of the glass, they would become scared and they would tense up and be afraid to move. However, when they were moved to the shallow side they would relax and jump onto the visually shallow surface.[1] This showed that visual sense, instead of the ability of the animal to feel the stableness of the glass, was in control.

Criticisms[edit]

One of the criticisms of the visual cliff study was whether the research in the study really supported the hypothesis that depth perception was innate in humans. One issue was about the glass over the deep part of the visual cliff. By covering up the deep side with glass the researchers enabled the babies to feel the solidity of the glass before they would cross over. This response was repeated over and over again in tests.[11] Another criticism has to do with the experience of the infant. Infants who learned to crawl before 6.5 months of age had crossed the glass, but the ones that learned to crawl after 6.5 months of age avoided crossing the glass. This helps support the hypothesis that experience does influence avoidance of the glass, rather than just being innate.[12]

See also[edit]

Visual Cliff Experiment Video

References[edit]

- ^ abcdeGibson, E.J.; Walk, R.D. (April 1960). 'Visual Cliff'. Scientific American. 202 (4): 64. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0460-64.copy

- ^ abLin, Yuan-Shan; Rielly, Marie; Mercer, Vicki S. (2010). 'Responses to a Modified Visual Cliff by Pre-Walking Infants Born Preterm and at Term'. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics. 30 (1): 66–78. doi:10.3109/01942630903291170.

- ^Cite error: The named reference

Henrywas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^Cherry, Kendra. What Is a Visual Cliff? psychology.about.com.

- ^Watch Out For The Visual Cliff. The Neuron (29 March 2009).

- ^Campos, J. J., Langer, A., & Krowitz, A. (1970). 'Cardiac Responses on the Visual Cliff in Prelocomotor Human Infants'. Science. 170 (3954): 196–7. doi:10.1126/science.170.3954.196. PMID5456616.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^maternal emotional signaling

- ^Gibson, E. J., Walk, R. D., & Tighe, T. J. (1957). 'Behavior of Light- and Dark-Reared Rats on a Visual Cliff'. Science. 126 (3263): 80. doi:10.1126/science.126.3263.80-a.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^ abcFantz, R.L. (1961). 'The origin of form perception'. Scientific American. 204 (5): 66–72. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0561-66.

- ^Arnold, N. A., Ng, K. T., Jongman, E. C., & Hemsworth, P. H. (2007). 'Responses of dairy heifers to the visual cliff formed by a herringbone milking pit: evidence of fear of heights in cows (Bos taurus)'. Journal of Comparative Psychology. 121 (4): 440–6. doi:10.1037/0735-7036.121.4.440. PMID18085928.CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list (link)

- ^[1] Adolph, K. E., & Kretch, K. S., Infants on the Edge: Beyond the Visual Cliff, Adobe PowerPoint

- ^[2] Nancy Rader, Mary Bausano and John E. Richards, On the Nature of the Visual Cliff Avoidance Response in Human Infants, Adobe PowerPoint